The first question visitors to the Adachi Museum of Art ask, indeed the one they most often ask, is why there are so many works by Yokoyama Taikan. Visitors also seem puzzled by the Japanese-style garden, as though it is a mystery for such a magnificent garden to be located here in such a rural setting.

The answer to both puzzles lies with Adachi Zenko, the museum’s founder. Adachi felt a strong resonance between the sublime sensibility of the Japanese-style garden and the paintings of Yokoyama Taikan which he wished visitors to experience. Adachi constructed his Japanese garden with the hope that through its seasonal expression of natural beauty visitors would be inspired to view Taikan’s paintings with a renewed sense of appreciation. This new appreciation would then lead to increased interest in the works of other Japanese painters, fulfilling Adachi’s hope that visitors would be “moved by beauty.”

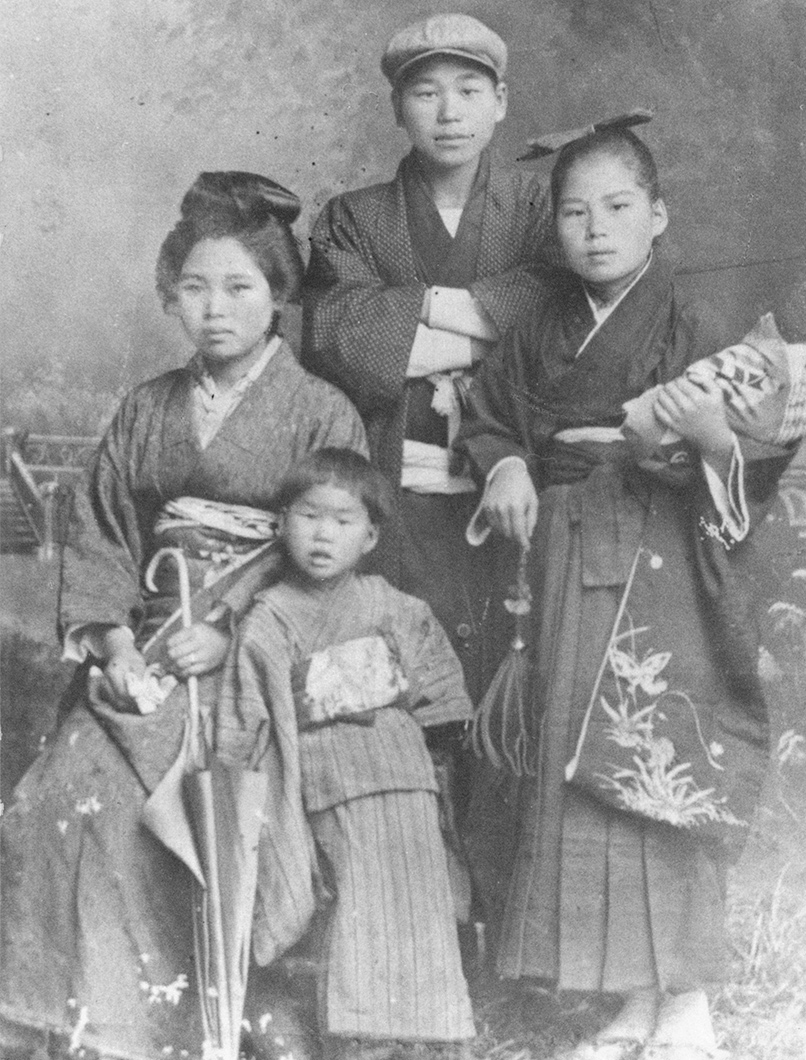

Adachi Zenko was born on February 8, 1899, in Iinashi Village in what is now 320 Furukawa-cho, Yasugi City, Shimane Prefecture, the site of the museum. Immediately after primary school, he went to work on his family’s farm, but seeing that his parents’ hard work was to no avail, he resolved to become a merchant.

At age 14, he took a job hauling charcoal by handcart from the countryside, near where the museum stands today, to the port of Yasugi 15 kilometers away. One day it occurred to him that he could probably sell charcoal to the people living along his route, so he ordered extra, which indeed he was able to sell. When Adachi discovered that he could double his income this way, he became interested in business. Throughout his life, this interest in business was expressed in many ways. He became a textile wholesaler in Osaka after World War II, and also dabbled in real estate. At the same time, he began collecting works by Japanese painters, something he had loved since his youth, and eventually became known as an art collector.

Designing gardens, something he had loved above all else since his youth, became a passion. Finally, in 1970, at the age of 71, as a way of showing gratitude to his hometown and to enhance the cultural development of Shimane Prefecture, Adachi established the Adachi Museum of Art.

Adachi’s passion for collecting art was well known, but perhaps his greatest accomplishment was his 1979 combined purchase of several Taikan works from the Kitazawa Collection, including Autumn Leaves, Mountain after a shower, and Summer.

When he first saw Autumn Leaves, a pair of six-panel folding screens, at the Exhibition of Yokoyama Taikan in Nagoya in 1978, its beauty took his breath away. Seeking to learn more about this work, he discovered that it was a part of the elusive Kitazawa Collection, known as the “phantom collection” because few of the artworks had ever been exhibited. The administrator of the collection at the time was also in possession of nearly 20 other Taikan’s works, most of which had been entered by the artist in various competitions and were therefore relatively well known.

Even more surprising was that the collection contained Mountain after a shower, a work that Adachi had long fascinated over, framing a reproduction he had cut out of a book. After two years of tough negotiating for these works, the collection’s administrative committee declared at the last minute that they wanted to remove Mountain after a shower and Summer from the works on sale. For Adachi, this was tantamount to heartbreak, and he made an impassioned plea to the committee. In his autobiography he described the moment thus: “It was as if I had fallen in love with a geisha at first sight, and then, after seeing her regularly for two years, all the while negotiating the price for her release, watching her run away clutching her pillow on the night of the nuptial rites.” He eventually convinced the committee to sell him the works.

In his autobiography, Adachi wrote:

“I hear the Adachi Museum of Art sometimes referred to as the ‘Taikan Museum of Art.’ This maybe because the masterpieces of Yokoyama Taikan are a glorious achievement in modern Japanese painting, and his works are in a great many collections. The core of the Adachi collection is certainly modern Japanese paintings, but it is Taikan who stands out in terms of quantity and quality. The recognition he has earned is for me justification of a long-held personal belief in his greatness. In short, it is Taikan’s ideation and expression that make his art so wonderful and inimitable. His engagement in life’s challenges with energy and a truth-seeking spirit give his works power, depth, and compositional integrity. People say that such a painter comes along only once every 100 years, or even 300 years. It is strange indeed that a dropout like myself feels so strong a connection to so great a painter! In terms of disposition and preparedness toward life, nothing would make me happier than to resemble him even in the slightest.”

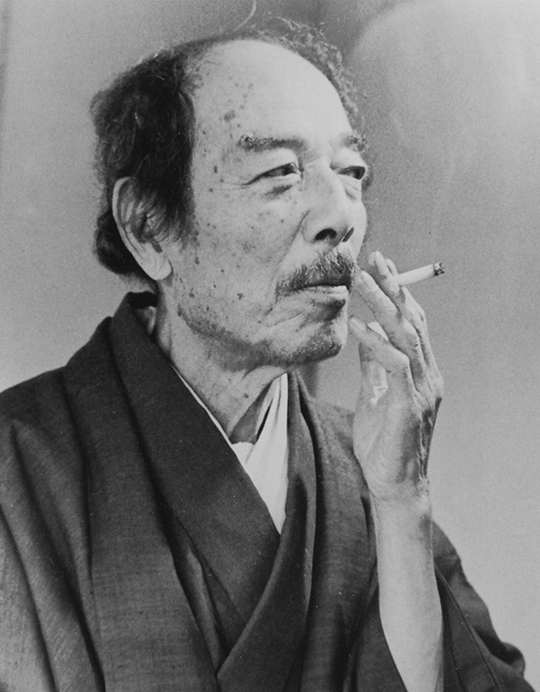

With great vigor, Taikan almost singlehandedly revived the Japan Art Institute, producing one masterpiece after another, year after year. At the age of 14 or 15, Adachi hauled a cart through the snow wearing only flimsy straw sandals, later emerging from these humble beginnings to become the largest owner of Taikan’s paintings in Japan. Perhaps the two had much in common beyond the obvious hardships they faced. Innovative ways of thinking, deep creativity and natural dynamism: in these ways perhaps they were similar.

For example, Taikan revolutionized the Japanese art world by developing a painting technique called karabake brushing paint dripped on a wet surface with a dry brush. Adachi, claiming to have no knowledge of the management of museums, devised a groundbreaking way to operate the museum such that it attracts more than 600,000 visitors annually, making it one of Japan’s leading museums in terms of visitor numbers.

Neither was bound by convention, and the two men were kindred spirits in their free thinking. One can also see their expanse of vision in the great breadth of Taikan’s works and the inexhaustible diversity of Adachi’s ideas.

However imposing and serious he may have been, Taikan always had the courtesy to see to the door young picture framers who worked with him, even when he could barely stand up after a night of drinking. For all the single-minded drive of Adachi, he had the humility to ask the people around him, some so young they could have been his grandchildren, for their opinions.

No matter how busy, he would make notes the day before for an interview of just a few lines in a local newspaper. He would banter with reporters and make them feel welcome, afterwards collapsing with exhaustion. The two men had such thoroughness in common.

Morning and evening Adachi would view his garden, and if anything appeared odd, however small, the gardener would be called in. Always the hands-on type, he had such fervor for art.

Once he talked about a painting he had failed to acquire, saying “Coming into contact with a masterpiece is just like meeting a person. It is fate. Collecting paintings is not about money. It is not about price. When a great painting is up for sale, you should close your eyes and grab it. I feel really bad about that painting. Even now I sometimes wake up at night with a start, remembering it, and then can’t fall sleep again.”

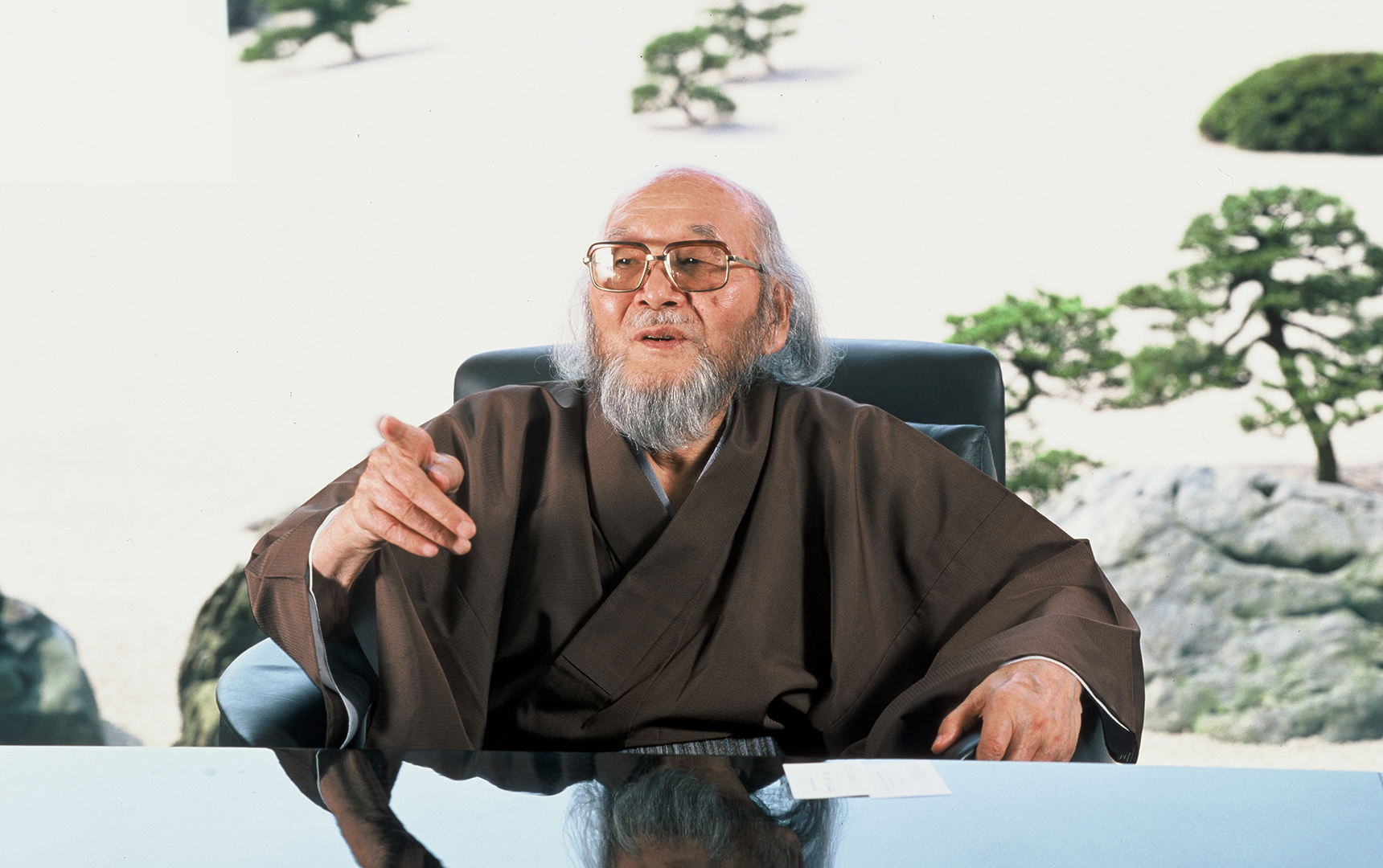

Adachi Zenko passed away in 1990 at the age of 91, carrying to his ultimate twilight the fulfillment of his dream of presenting the Adachi Museum of Art to the world. When I recall his passion, one realizes that it is not just the paintings or the garden or even the people that Adachi wanted us to encounter at the museum. It is his wish for the touching of our hearts by the beauty that permeates every corner of the Adachi Museum of Art. For every visitor to take in the beauty and be moved by it was the founder’s simple wish in establishing this art museum.